Most improvisers use scales that contain either 7 or 5 (pentatonic) notes. This will probably be sufficient to improvise over most songs in a large variety of styles. In part one and two of this column, we will look at ways to create scales that are not the standard ones people learn.

First, let's look at those that are the ones that are usually taught, and make sure you are solid on that as well. These include the modes of all these scales, but I will not list them (if you do not know what a mode is-find out!) For each of these you should also know the modes, and the difference between playing in a Modal Key, and simply playing a modal scale, which I do not differentiate from its parent scale.

The ones you should definitely know, (including all the modes on the scales that have possible modes) are: The major scale, natural minor, harmonic minor, melodic minor, chromatic scale, basic pentatonic minor and major scale as well as the blues scale, whole/half and half/whole step diminished scale, and the whole tone scale. Those are the ones most people learn and occasionally one or two different ones, if anything more. Remember, these scales alone, if you include the modes that are built on each degree of the scale, will generate a lot of scales to learn alone. A good example to listen to modal music is the Miles Davis classic, "Kind of Blue".

On a side note: Personally I believe you should you should also to learn to play each scale from each degree (note) from any finger. The only problem is one of the four fingerings for each scale will not be practical. The one of four fingerings that is somewhat awkward is worth exploring. The fingerings I have been talking about are considered "in position", meaning if the scale is played at the fifth fret, only the first and fourth fingers of the left hand will do any stretching. Learning all of these scales in position is a lot of work alone, there are also more ways than I can count to finger any scale where there are position shifts. One could play a scale on one string, or with multiple position shifts if that is the desired fingering. Personally I think it is best to first learn them "in position", which will help you locate the notes all over the finger board in a systematic way.

As all of this becomes second nature, you may make choices for certain reasons on occasions. For example I often take a melodic line that could be fingered easily, but because the same note can be found so many places on a guitar, I will chose the notes based on their timbre, which can make an enormous difference. To see what I mean, play your high E (first string) open and listen to it carefully. Then go to the 14th fret on your fourth string and listen to the difference. Both are the identical note and would be written the identical way in standard music notation. They definitely do not sound the same. There are five of these particular Es on the guitar, and on some guitars with longer necks six places to play this E note, but none of them sound the same. At a more advanced level, whether one wants a thick or thin sounding note will dictate where it gets fingered. This "overlapping" of notes, is what makes the guitar a difficult instrument to sight read on. A piano only has one place to play that high E. So now let's get back to the subject of creating scales.

Mathematically we know there are 12 notes in the quarter tone system of music, and harmonically extensions that can go all the way up to a 13th of a chord.

Knowing these two things, it is possible to create scales that are larger than the standard 7 or 5 notes per octave scales, and sometimes they may occupy more of the fingerboard than usual just to play them at all.

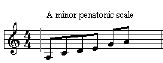

Most players use the minor pentatonic (simply any 5 note scale), but a pentatonic scale can be created for any situation. Let's look at this first.

The most commonly used pentatonic scale in most music styles is the minor pentatonic scale (and its "modal scales"). To keep things simple, we will use the key of A for these scales. Here is the popular minor pentatonic scale, Note that the flat third (the C natural) is what makes it a minor scale.

(This would go from the A on fret 5 to the C on fret 8 to compete the scale, which is slightly over 2 octaves.)

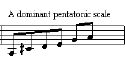

As previously said, any 5 note scale can be considered a "pentatonic" scale. Most players stick to the standard scale, but a pentatonic scale can be created to fit any type of chord. Here is one that would fit nicely over a dominant chord. (Only one octave is shown but you can easily expand it to longer lengths, and octaves on the guitar.)

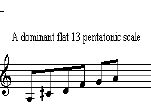

Here is one more that would work over a dominant chord with a flat

13th or an augmented chord (technically synonymous chords.)

Part two of this column will explore scales that can go up to thirteen notes, or take over two octaves to complete. In this lesson, what is important is that you get the idea.

Note: You must first have all the mentioned basic scales learned first all over the neck. That is standard guitar knowledge now in the year 2002, and even earlier. The standards for guitarsts have escalated to a great degree. In the late '60s, many could easily sound fantastic by simply wailing on the minor pentatonic scale mentioned above. Sometimes, I am amazed at how much the skill level expected of a guitarist has changed. It should, since other instruments have been so much more harmonically and melodically more advanced.

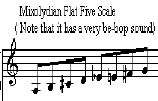

Here are a few to get you started. They will only be written in one octave, so figure out how to at least go to two octaves, always landing on the highest note possible, even if it is not the root!

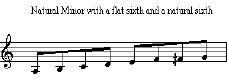

Here is one more of the minor scale type. Normally, the natural minor (try to study relative majors and minors - it will help in you trial improvisations with this scale), has a flat sixth. In this 8 note scale we are going to have a natural and a flatted sixth.

Again only one octave is shown. A slight bit over two octaves can be played

once again. The biggest reason that comes to mind is that the root is not necessarily a note of choice, so you want as many notes in the scale fingering you are using to be available.

This will be enough before we tackle the harder scales that also have more notes. Remember to expand these to "in position" over two octave scales.

If you have a sequencer lay down a grove so you can develop melodic ideas with these scales. If you don't, tape yourself playing one (preferably with a metronome going in some sort of headphones). This is important for two reasons. You need to learn to develop ideas with these scales. Reason two is that you can always use practice playing in time.

In the next column we will tackle more complex concepts with this. Hopefully, this will give some or a lot of ideas to start off with. Happy playing!

P.S. Not to plug my own records, however the last one ("Strange And Savage Tales") makes use of all sorts of these type of scales. A new one is on the way.

The late Colin Mandel was a guitarist out of Los Angeles and a graduate of the Berklee College Of Music.

During his career he had been featured as new talent in Guitar Player and Guitar World Magazines.

His instrumental CD is entitled "Strange and Savage Tales...".